Halfbreed

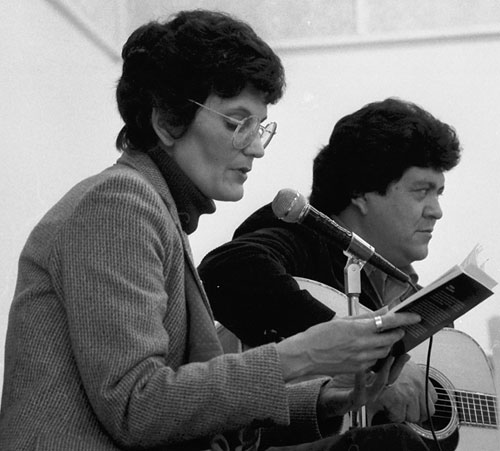

Halfbreedby Maria Campbell

One of these people was Eugene Steinhauer. He had nothing when he came to AA except the clothes on his back. He had lived on various skid rows and his family had given him up for a derelict. Now he was finding sobriety, as well as hope for himself, and a future as something more than just another drunken Indian. I admired him because he was the first Indian I had ever met who let white people know how he felt about them, not just by his attitude, but verbally as well. I'd hated those nameless, faceless white masses all my life, and he said all the things I had kept bottled up inside for so many years.

At this time, I felt Eugene could do no wrong. He was one of the "brothers" Cheechum had talked about. When, following his example, I too began to speak out, his attitude towards me changed. At the time I was hurt and discouraged because to me he was a special person, but it doesn't matter anymore. Since then I've met many Native leaders who have treated me the same and I've learned to accept it. I realize now that the system that fucked me up fucked up our men even worse. The missionaries had impressed upon us the feeling that women were a source of evil. This belief, combined with the ancient Indian recognition of the power of women, is still holding back the progress of our people today.

In Maria Campbell's autobiography, Halfbreed, her project is to show Métis life from the days of Riel through to the 1970s. In this striking book, Campbell forces the white reader to confront the results of cultural imperialism and policies such as the Indian Act, and demands that the reader look face-on at the resulting poverty and crisis of identity, self-hatred and pain. For Aboriginal and Métis readers, Campbell strikes out at the white structures of power, names and shames the oppressors, and puts forward a challenge to other Aboriginal and Métis women to tell their own stories. The purpose of Halfbreed, then, is twofold: white readers are shown the results of their cultural practices, and Aboriginal and Métis readers are given a literary history to write into and respond to.

The life Maria Campbell recounts in her novel is a difficult one. She moves from being a strong child swearing to her grandmother that she would never cower in front of white people, to a young teenager thrown into the role of mothering her brothers and sisters with the death of her own mother and living in constant fear that children's aid workers would separate her family, to a young wife living in a horribly violent marriage, to a prostitute and drug user living in Vancouver. When Campbell finally begins to clear her life up, she meets a man she loves, but her inability to be honest about her past and her shame at the life she has lived leads her to a mental breakdown. At the end of the novel, we are met with a politically active Maria Campbell, standing on her own two feet, raising her own children, and rebuilding a relationship with David. But we never again have the hopeful and potent Maria Campbell who opened the novel -- that wide-eyed childhood idealism is lost. That Campbell perseveres in spite of her loss of idealism is perhaps the most important lesson of the novel. To progress as a society, we must be able to see the situation as it really is but still maintain the will to try to change things anyway. That is Campbell's gift in this novel.

From the perspective of masculinity studies, this novel is an interesting one because Campbell is just as interested in Aboriginal and Métis men as she is in Aboriginal and Métis women. While the effects on women are perhaps more readily obvious through the cycle of victimhood they find themselves trapped within, the Native men who perpetrate these acts are not cast merely as one-dimensional villains. Campbell attributes her early maturation to the process of watching her father die inside as the family sank deeper and deeper into poverty. For Campbell, the real tragedy of these communities is that people have no reason to dream. A white child may grow up poor but be able to dream themselves out of it, Campbell argues, but a Métis child has had that ability to dream robbed from them. They can only imagine becoming a stereotypical 'drunken Indian,' as she terms it, or becoming the battered and abused wife of the same. With no prospects for fulfilling work and racism stopping advancement at every turn, Campbell's biggest wish for her people is to return to them the right and ability to dream of an alternate future. As one critic has dubbed it, this book is a call for an 'alterNative' approach to aboriginal identity and selfhood.

No comments:

Post a Comment